Inflation is back. But, as Oliver Kamm writes, it never really went away

Few voters follow the daily fluctuations of the gilts market. All, however, notice the effect on their incomes of a sharp increase in the price of staples like food, energy and rents or mortgages. Quite suddenly it has become the dominant conundrum of domestic policy in the advanced industrial economies, in part – though only in part – because of the dominant issue of international relations.

Russia’s brutal invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 gave a powerful stimulus to world commodity prices. This was not the only reason for a surge in inflation, far above the Bank of England’s target rate of 2 per cent annually. Indeed, UK inflation had already reached 7 per cent after a long period of huge government spending due to the pandemic, near-zero interest rates and supply-side constraints. But Russian aggression amplified these pressures already evident in the western economies.

In Britain, the short-lived government of Liz Truss added a further twist to the mix: the disastrous mini-budget of Kwasi Kwarteng, the even shorter-lived chancellor, caused investors to revise up their expectations of inflation. Unfunded tax cuts plus additional borrowing, without a parallel increase in supply, were bound to be inflationary: hence a rise in gilt yields, adding to the cost of mortgages and of servicing government debt. What one market strategist disparagingly but not unfairly (for the consequences of the mini-budget could have been predicted) termed “the moron premium” in gilt yields took some time to be unwound after the abandonment of this quixotic economic strategy and Truss’s departure from Downing Street.

Across the United States, Britain and the European Union, 12-month inflation rates either approached or reached double figures during 2022, for the first time in more than 40 years. The combination of accelerating inflation and sluggish growth in output recalled the “stagflation” that characterised the malaise of the advanced industrial economies in the 1970s. It augured, and imposed, severe pressures on living standards. The particular danger that the more responsible policymakers foresaw was that expectations of high inflation would become embedded in the decisions of consumers, employees and businesses. A spiral of higher wage demands, consequently increasing business costs, would thereby intensify the inflationary problem.

This is not a new set of quandaries. Yet debate continues on how far inflation is remediable and how damaging it is if allowed to persist. History provides no definitive answers but some perspective.

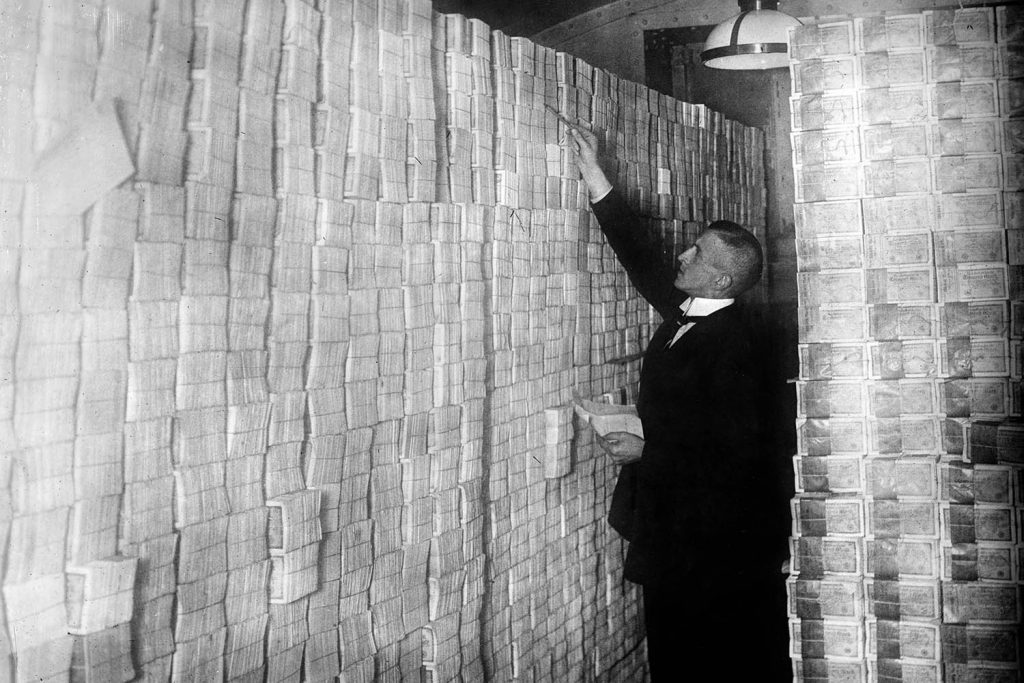

Price inflation has been a fixture of the post-war era, and its control has sometimes been the dominant issue of political debate, but it has not always been so. Though there are problems with estimating historical data, we know there have been times over the past three centuries when prices have fallen, notably in the wake of the Napoleonic wars and especially in the “long depression” of 1873–96. Conversely, the interwar period in the 20th century prompted the coining of a neologism, “hyperinflation”, to describe the collapse in the value of money in various European countries.

The best-known example is Weimar Germany: by the time price stability was restored at the end of 1923, the price level was roughly a trillion (that’s not a misprint) times that of the immediate pre-war period. It actually cost more to print banknotes than they were worth. Workers were commonly paid twice each day, as the real value of their pay had declined substantially by the afternoon.

It’s open to debate how far moderate rates of inflation – in the low single digits – are economically damaging. But the catastrophic effects of extreme fluctuations in prices are known.

Take, first, deflation. The long depression was not unique: prolonged falls in prices have happened periodically in the western economies, and as recently as the 1990s in Japan. Other examples include 1815–21, when world agricultural prices roughly halved, and the US banking panic of 1837, when the general price level fell by around a third. Deflation has predictably debilitating effects.

First, it undercuts consumption. If consumers expect prices of durable goods to be lower next year than this, then they will rationally defer spending, thereby intensifying the fall in aggregate demand.

Second, deflation will cause unemployment, as real wages rise and thereby raise business costs. This would admittedly not be true if workers accepted cuts in money wages while keeping real wages constant. But in practice this does not happen in modern economies. Wages, in the jargon, are downwardly sticky.

Third, there is the problem of the “zero lower bound” to interest rates, which is to say interest rates cannot go below zero. Hence, if prices fall, real interest rates must rise, creating what economists refer to as a liquidity trap, in which even interest rates of zero will not persuade consumers to resume spending. Fourth, deflation raises the real value of debt, thereby also preventing consumption and imposing severe hardship on borrowers.

All of these effects combined can be self-perpetuating, locking the economy into a cycle of contraction and stagnation. The banking crash of 2007–09 prompted fears that the advanced industrial economies would collectively suffer just this fate. Hence the extraordinary policies of near-zero interest rates and asset purchases by central banks, in an effort to stimulate demand. These, along with a rise in budget deficits to take the strain of recession, did prevent a repeat of the Great Depression, which many feared, but sustained growth remained elusive.

Conversely, high inflation inflicts immense damage long before it reaches hyperinflation (inflation of some 500 to 1,000 per cent a year or more, let alone at Weimar levels). Here are some of its effects, and not all of them are obvious.

First, the economy will inevitably have an excessively large financial system relative to output. This is because consumers and businesses will expend more time and resources in trying to preserve the real value of their cash holdings. Second, and partly in consequence, the economy will be more vulnerable to financial crises as the banking system adapts to high inflation. Third, the economy will be less efficient, as the signals given by shifts in relative prices for products, services and intermediate goods become much harder to interpret. Fourth, there will be a deadweight cost from frequent repricing of goods and services. And fifth, most significant, living standards are cut, with poorer households especially at risk.

These effects are especially salient in countries whose politics have fallen prey to populism. Such crises have been a recurring feature of the modern history of Latin America, but the same would have happened if the Syriza government in Greece that took office in 2015 had persisted in radical left-wing policies rather than belatedly submitted to the laws of arithmetic.

Sebastian Edwards, an economist with a Chilean background, has set out a theory of this cycle, which typically has four stages. First, expansionary policies secure a boost to output and real wages, while inflation is held down by price controls and a surge in imports. Second, bottlenecks in production emerge because there isn’t enough foreign exchange to pay for this pace of import expansion. Hence the government resorts to import controls and currency devaluation. And this is where inflation starts to pick up, which workers try to compensate for with higher wage demands.

After this, third, come shortages of goods, especially basic goods whose prices have been held in check by artificial price controls. A black market emerges and public sector wages are hiked to keep pace with inflation. The currency plummets and foreign exchange (inevitably the dollar) becomes the medium of transaction. Inflation soars and thereby crowds out productive activity (after all, consumers are spending most of their time queuing for staple goods that are hard to obtain). Real wages collapse and savings become effectively worthless. The fourth and final stage is the implosion of the economy and prolonged austerity.

This is the great damage that inflation can inflict. High inflation, let alone hyperinflation, doesn’t just make people poorer – though it certainly does that. It can destroy a social order by eliminating the middle class altogether. Only the very rich, by being able to repatriate their savings abroad, have any degree of insulation.

High inflation is disastrous but what of more moderate rates of inflation, in the single digits? This doesn’t have a definitive answer but since the 1990s policymakers in the advanced industrial economies have generally regarded inflation rates of above 2 per cent as a problem. And there are sound reasons for this. The difference between 2 and, say, 4 per cent inflation is not vast and in principle prices and wages could smoothly adjust to a world of moderate inflation. There would be some gainers (predominantly borrowers, including the government, as the real value of the debt would fall) and some losers (mainly creditors) but not to the extent of causing widespread penury.

The real difficulty is subtler, and it runs like this.

The reason the Bank of England maintains an inflation target at all is to provide what’s known as a nominal anchor. This means an instrument that gives credibility to monetary policy. It doesn’t have to be a formal inflation target.

When the government of Margaret Thatcher took office in 1979 (before the era of central bank independence), it originally tried to target the growth of the money supply as a means of controlling inflation. This approach was succeeded by the unannounced policy of Nigel Lawson, as chancellor, to target the exchange rate of sterling with the Deutsche mark. This then gave way in 1990, when John Major had succeeded Lawson, to formal membership of the European exchange rate mechanism (ERM), under which the fluctuations of member currencies were supposed to be kept within certain bands. And when sterling ignominiously exited the ERM in 1992 amid intense speculative pressure, the government (with Major now prime minister) found its monetary policy in tatters. This was when it chose to target inflation directly, as its nominal anchor, in line with the policies of some other western economies (the approach had first been introduced in New Zealand). The incoming Labour government in 1997 cemented this approach by giving the Bank of England operational independence to meet an inflation target.

Should the Bank’s target be raised to, say, 4 per cent, the risk would be that the nominal anchor would lose credibility. Consumers, businesses and investors might then expect the target to slide progressively upwards, perhaps to 5 and then 6 per cent. They would adjust by seeking to protect themselves from the effects of higher inflation. And so the costs of inflation would take hold long before inflation itself reached the sort of levels they attained in 2022.

If inflation is this damaging, why then have central banks not taken more vigorous action to get it back to target? And indeed why have an inflation target even as high as 2 per cent? The answers to these questions go to the heart of modern monetary policy, and were they better understood then central banks would be less easy prey for populist politicians, as was sadly evident during successive Conservative leadership contests last year.

Inflation targeting is a relatively recent innovation in monetary policy. Indeed, the problem that governments sought to resolve in the immediate post-war period was how to maintain output and employment rather than return to the devastating deflationary slump of the 1930s. The great text of the time, John Maynard Keynes’s The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money (1936), has very little to say about inflation. Keynes certainly recognised the potential problem, noting that: “When full employment is reached, any attempt to increase investment still further will set up a tendency in money-prices to rise without limit …” To guard against this, he anticipated that a government would curb its expansionary policies before full employment had been reached. But he was inclined to see inflation as a problem of politics rather than economics. Nor did his theories explain the puzzling coexistence of inflation and unemployment as the post-war expansion proceeded.

A highly influential approach to inflation was proposed by the economist AW Phillips in 1958, when he plotted in a scatter diagram the rate of change of money wages against the level of unemployment for the best part of the previous hundred years. It appeared to suggest that there was an inverse relationship between the two. Hence higher unemployment meant lower inflation, and vice versa. The policy implication was that economic management required trading off unemployment against inflation.

Almost as soon as this statistical relationship was discovered, it ceased to be applicable. In the 1960s and, with a vengeance, the 1970s, western economies suffered high inflation and high unemployment simultaneously. And the ambitions of policymakers began to be scaled back. Increasingly, inflation was seen to be the principal issue of economic management, resulting eventually in the policy of directly targeting it as a variable. As Nigel Lawson put it in his huge memoir, The View from No. 11 (1992): “[W]hen inflation did start to take off at the end of the 1960s and the early 1970s, my perspective swiftly changed. It was clear to me that the overriding object of macroeconomic policy must be the suppression of inflation.”

This belief was not limited to economic liberals. It progressively became conventional wisdom from the late 1970s, and led eventually to the adoption of inflation targeting. Central banks that operate inflation targeting aim for price stability. This is not the same as zero inflation. There are good reasons for a slightly positive inflation target. First, there is a problem of measurement. Raw statistics are inevitably rough. They cannot easily make allowance for changes in the quality of a good, or at least not for many goods at the same time. And broadly, a small dose of inflation has advantages over a small dose of deflation. It acts as an economic lubricant by, for example, encouraging entrepreneurs who believe they can make productive use of scarce capital and generate returns on it above the interest they pay for it.

The problem arises, as is evident now, when inflation is far above this low and positive target. It has become a cliché for politicians, especially in an embattled British government, to criticise the Bank of England for allowing inflation to be several multiples of the target, but in fact the Bank has acted sensibly and in line with its own mandate. Inflation is high in the western economies not because of excess demand but primarily because of a huge supply-side shock. And getting inflation rapidly back to target when there is such a shock (in this case, energy prices) may have very big costs in lost output and jobs.

An inflation-targeting regime is not a mechanical rule, requiring interest rates to go up whenever inflation is above target. It is, rather, a framework within which policymakers exercise a measure of discretion (“constrained discretion”) in how fast they seek to get inflation back to target. If they do it quickly, they may consign the economy to an unnecessary recession, and indeed they may not even be successful. Crushing domestic demand by raising interest rates to, say, 7 or 8 per cent would not directly affect the price of energy imports.

The difference between a rule and a framework is exemplified in one of the worst economic policies that still surfaces in current debate (even though it is admittedly a small minority opinion): the gold standard. High inflation during the First World War persuaded British governments thereafter to peg sterling to the price of gold at the pre-war parity. It did this in 1925, with disastrous consequences. Defending a quite arbitrary level of sterling ensured that monetary policy had to be far too tight, causing a collapse in output and employment, and severe deflation, even before the Great Depression.

The current system is hence different in principle as well as specifics. And there is nothing sacrosanct about the Bank’s mandate or its target. It’s reasonable to examine these in the light of experience. That is the best case you can make in defence of Truss when she said, while running for the Conservative leadership last summer, that she wished to “change the Bank of England’s mandate to make sure in the future it matches some of the most effective central banks in the world at controlling inflation”.

But in truth Truss’s words were not really a counsel to examine evidence; they were more a sly insinuation that voters’ problems with the cost of living were the Bank’s fault rather than the government’s. If politicians are to tighten the constraints on monetary policymakers, forcing them to treat the inflation target as something more akin to a mechanical rule, there will be costs. At a minimum, it will suggest to financial markets that politicians are more likely to meddle in monetary policy in future, which will create uncertainty and thereby cause investors to demand a higher premium to be persuaded to hold sterling-denominated assets.

It would be invidious, and almost certainly swiftly refuted, to proffer a forecast of where inflation will now go, so I won’t attempt it. Instead, I’ve sought to explain why inflation is a problem, how policies have evolved to deal with it, and why the current set-up of an independent central bank targeting inflation is a sensible one.

The system admittedly has lacunae: for better or worse, inflation targeting has not, for example, prevented asset-price inflation. Indeed, aggressively easy monetary policy from 2009 to 2022 did much to stimulate it. It is conceivable that a future British government of right or left might dilute inflation targeting by mandating the Bank of England to pursue other goals alongside it or perhaps in place of it. This would not be sensible, but it would be in keeping with the romantic misconception, exemplified in Britain’s departure from the European Union, that all things are possible if only they are wished for, and that nothing of ill consequence will thereby arise.

This piece was taken from the next edition of Tortoise Quarterly, our short book of long reads, to be published in June. You can browse previous editions and pieces here.

Photograph Getty Images