Guyana is booming and Venezuela wants a piece of it.

Last month Boris Johnson interrupted a Caribbean holiday to fly by private jet to Venezuela to try to persuade its autocratic leader to stop helping Russia in Ukraine and threatening his neighbour in Guyana.

So what? Johnson is an unlikely freelance peacemaker, but Guyana is an exceptionally tempting target for a tyrant. It is

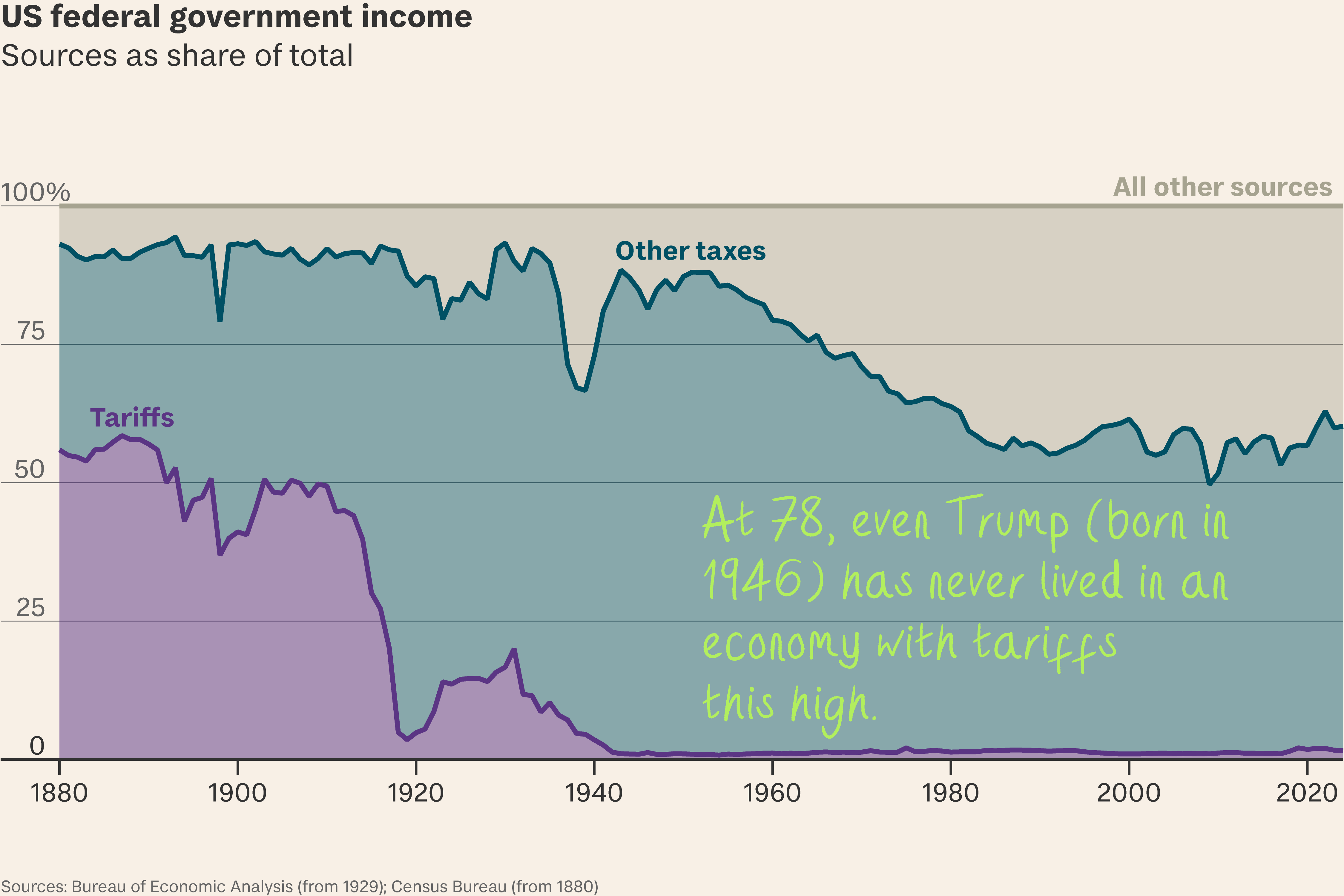

- the world’s fastest-growing economy;

- expected to produce as much oil as Nigeria by 2028; and

- a study in how not to bypass fossil fuels en route to net zero.

Guyana is also one of the most vulnerable countries in the world to the effects of climate change, and a member of the Commonwealth.

Target Essequibo. Since Exxon struck oil off its coast in 2015, Guyana’s bonanza has brought:

- Unwanted attention from its Venezuelan neighbour, which is claiming the oil-rich Guyanese region of Essequibo.

- A gusher of prosperity, with oil paying for new roads and schools while new hotels spring up across the capital of Georgetown.

- The embrace of oil in a country that once championed the fight against climate change.

Sweet and light. Guyana pumps about 645,000 barrels per day at present, up from zero three years ago. It expects that to double in the next four years as the 11-billion barrel offshore Stabroek field comes onstream, and can count on easy access to world markets because it produces “light, sweet” crude, which requires less energy-intensive processing than the more viscous types in Venezuela’s reserves.

Upside. GDP growth peaked at 67 per cent in 2022 but is projected to go on growing at 20 per cent a year for the next four years. Per capita GDP has more than quintupled since 2015.

Down. Around 800,000 people live in Guyana, mostly along the coast, which is – in places – around two metres below sea level. That puts it at high risk of flooding and the intrusion of saltwater inland, which makes it harder to farm.

Carbon sunk. Guyana’s substantial forest cover and lack of heavy industry mean it’s actually carbon negative. Before the oil came, it tried to make the most of that natural wealth, striking a $250 million deal with Norway to protect its forests. But that’s dwarfed by oil. Government income in taxes and royalties is expected to hit $4.2 billion annually by 2025. Ironically, it may now use its oil money to help with the green transition.

Reverse transition. This is not how humanity was supposed to wean itself off hydrocarbons. The falling cost of renewables and the climate imperative was meant to deliver a low-carbon economy, which is starting to emerge in rich countries but not in less developed ones – until now.

Guyana is a new type of producer with huge forests and fossil fuel reserves, trying to align its green and brown identities, says Valerie Marcel, an associate fellow at Chatham House. It has a plan to reinvest oil revenues in low carbon industries, but there’s a temptation to grab more of the value from oil extraction; it’s also looking into building an oil refinery.

Venezuela. Not satisfied with the world’s largest oil reserves, Venezuela has laid claim to Essequibo – rich in both oil and forest cover and accounting for two thirds of Guyana’s territory – for a century. This is not just talk:

- Last December Venezuela’s President Nicolás Maduro threatened to annex the region.

- Satellite pictures have shown a build-up of Venezuelan forces at the border.

Next Kuwait? Maduro has since said he’ll pursue peaceful avenues to resolve the border dispute. Even so, a Royal Navy patrol ship visited Georgetown before Christmas and the US has promised increased military assistance. Johnson’s spokesman said his flying visit to Caracas, first reported by the Sunday Times, was partly aimed at defusing tensions.

What it won’t do is defuse the tension between oil-fuelled development and the planetary need to reduce emissions – although money just might. Marcel says Guyana’s oil revenues are so high it may be able to fund adaptation to climate change and the transition to a low carbon economy without external help.

What’s more. Namibia could be next. It too has about 11 billion barrels of untapped oil reserves off its coast.

More than 70 countries are holding elections this year, but much of the voting will be neither free nor fair. To track Tortoise’s election coverage, go to the Democracy 2024 page on the Tortoise website.