It isn’t affordable, and it isn’t getting people into work

Next week the government wants to close a fiscal hole in the Office for Budget Responsibility’s forecast. Its original plan was to do this by cutting between £5 billion and £6 billion from the welfare bill, with a particular focus on disability benefits.

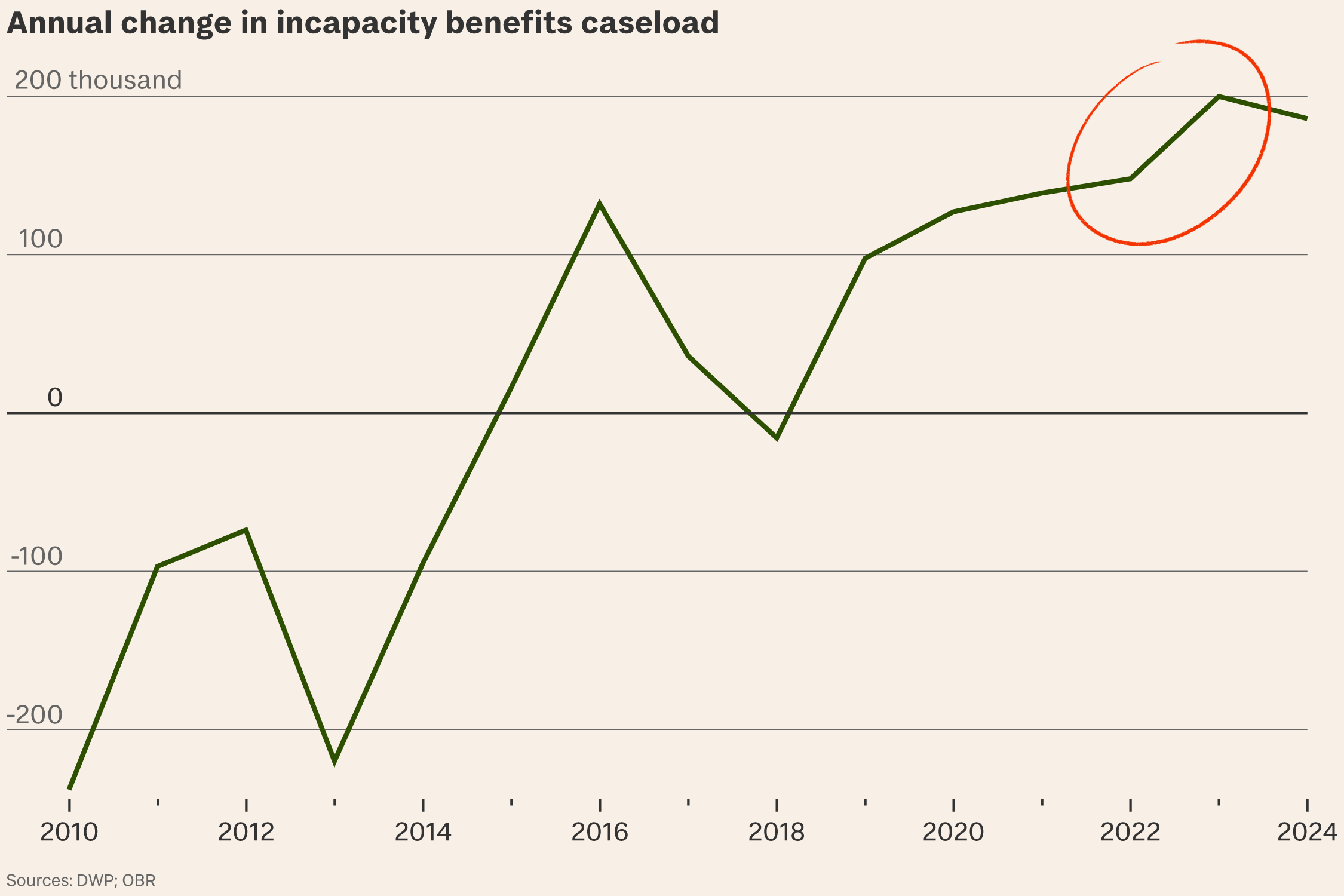

So what? The number of working-age people receiving long-term sickness or disability benefits has grown significantly since the pandemic, up from 2.8 million to four million, or from one in 13 to one in ten of the working-age population. With question marks over whether the country has really got that much ‘sicker’ this system is ripe for reform. But it won’t be easy.

- The government is facing a backlash from MPs who didn’t come into politics to oversee a return to “austerity” – a Cabinet revolt may yet water down the plans.

- The threat of judicial review makes pressing ahead with significant reform without consulting beforehand risky, bordering on impossible…

- …and yet the OBR normally only scores savings from firm government policies and not options within a consultation paper.

Scale. The benefits system as a whole is vast and extremely costly but designed to provide a safety net below which no one should fall. Broadly speaking it is made up of

- pensioner benefits like the state pension and winter fuel payments;

- cash for those who are out of work or cannot work via Universal Credit; and

- support with the additional costs of long-term illness or disability in the form of Personal Independence Payments.

Overall the OBR says the UK spends 11 per cent of GDP on all social security and welfare.

Can’t touch this. Of these, the government has ruled out making any changes to the Triple Lock. This means the state pension will continue to rise by whichever is highest out of inflation, wages or 2.5 per cent. Think tanks on both the left and right argue that this is unsustainable, but it remains politically untouchable.

PIP PIP. As Keir Starmer points out, spending on incapacity and disability benefits alone is set to rise to £70 billion a year. This is partly, but not entirely, driven by an increase in those claiming for mental health conditions. The Institute for Fiscal Studies reports a 24 per cent increase in so-called ‘deaths of despair’ (attributed to alcohol, drugs and suicide) in 2023 compared with pre-pandemic levels, but there is little hard evidence that working age people are getting physically sicker. What is clear is that reform is needed. Options should include

- replacing ongoing payments to those who need aids or appliances with one-off grants to pay for the cost of this equipment;

- reviewing eligibility criteria, particularly for those with mental health conditions, to ensure the system is sustainable;

- providing treatment rather than cash if that is the best way to help some people; and

- aligning benefits rates and incentives across the system so it always pays for someone to work.

JR v the OBR. These options require fundamental reform and as such proper consultation. But the government could deliver significant savings far higher than the £5 billion to £6 billion being mooted. Pressing ahead with some of these measures without consultation might well enable the OBR to score some savings at this fiscal event and therefore help Rachel Reeves meet her fiscal rules. But they would leave the government at risk of losing a judicial review, which happened recently with changes to the Work Capability Assessment. Such a loss would blow a hole in a future Budget.

Cuts not reform. More likely therefore on 26 March are simple and crude cuts to rates, which the OBR can score now with the promise of future consultation on reform. Such cuts can mainly be implemented through secondary legislation although some disability benefits might require primary legislation. But these cuts have provoked the most outrage from MPs and ministers.

A missed opportunity. If the government does backtrack on reducing the overall bill or ignoring more controversial reforms it will be a missed opportunity. Fraser Nelson and others have argued that welfare reform might provide the government with a domestic policy agenda that has so far been absent.

But… even sticking with their current plans and shaving a fraction of the £200 billion benefits bill simply to meet the fiscal rules won’t provide that agenda, just more of the penny pinching Labour used to lay at the feet of the previous government.