They’re second only to the US in world rankings, but job cuts threaten what made them among the world’s best.

The University of Essex has warned staff it’s delaying promotions and reviewing future pay awards to cope with a potential £14 million budget shortfall blamed chiefly on a 38 per cent decline in international postgraduate student numbers.

So what? Essex is not alone. The UK’s universities are running out of money.

Cuts are being made across the sector as frozen tuition fees, high inflation and falling international student numbers hammer finances. According to John Rushforth at the Committee of University Chairs, university bankruptcy is a realistic possibility.

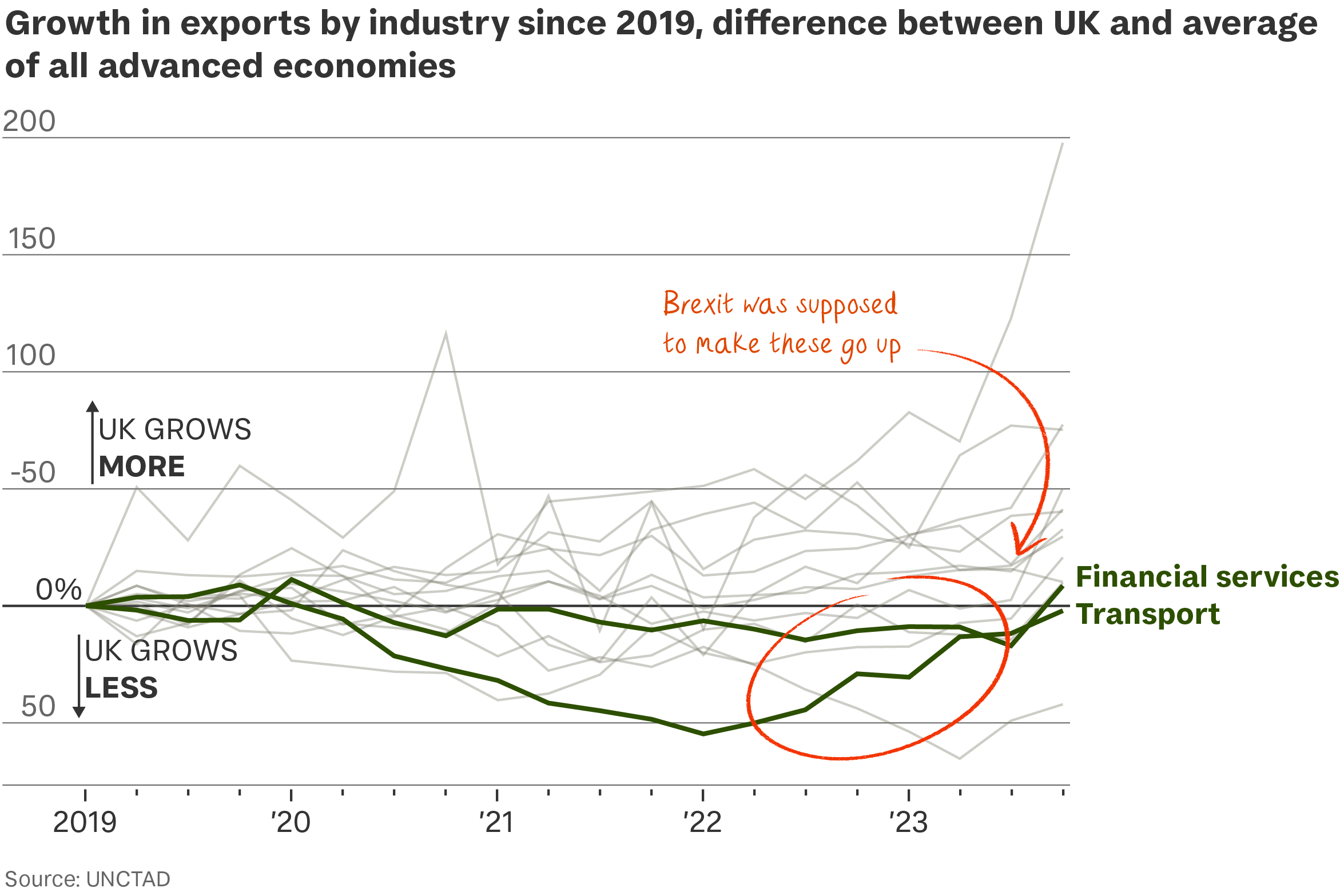

The broader picture is of a long-term policy failure threatening British

- exports – the UK’s 144 universities contribute £130 billion to the economy, which is more than farming, forestry, fishing, mining, arts and entertainment combined;

- soft power – mandarins and business leaders say British universities are in danger of losing their enviable position in global rankings; and

- university standards – because low student-teacher ratios that traditionally sustained standards are now at risk as universities struggle to stay afloat.

At stake. Seventeen of Britain’s universities are in the top 100 of the QS World University Rankings, second only to the US. In 2012, the UK accounted for 15 per cent of the world’s most-cited research papers, down now to 11 per cent. Regional cities rely on universities to bring high-wage jobs to their local economies. In 2020-21, more than 21,000 startups were spun out of UK universities.

At risk. So far this year 20 institutions have announced job cuts to limit looming deficits, including the universities of Winchester, Surrey and Queen Mary University, London last week alone.

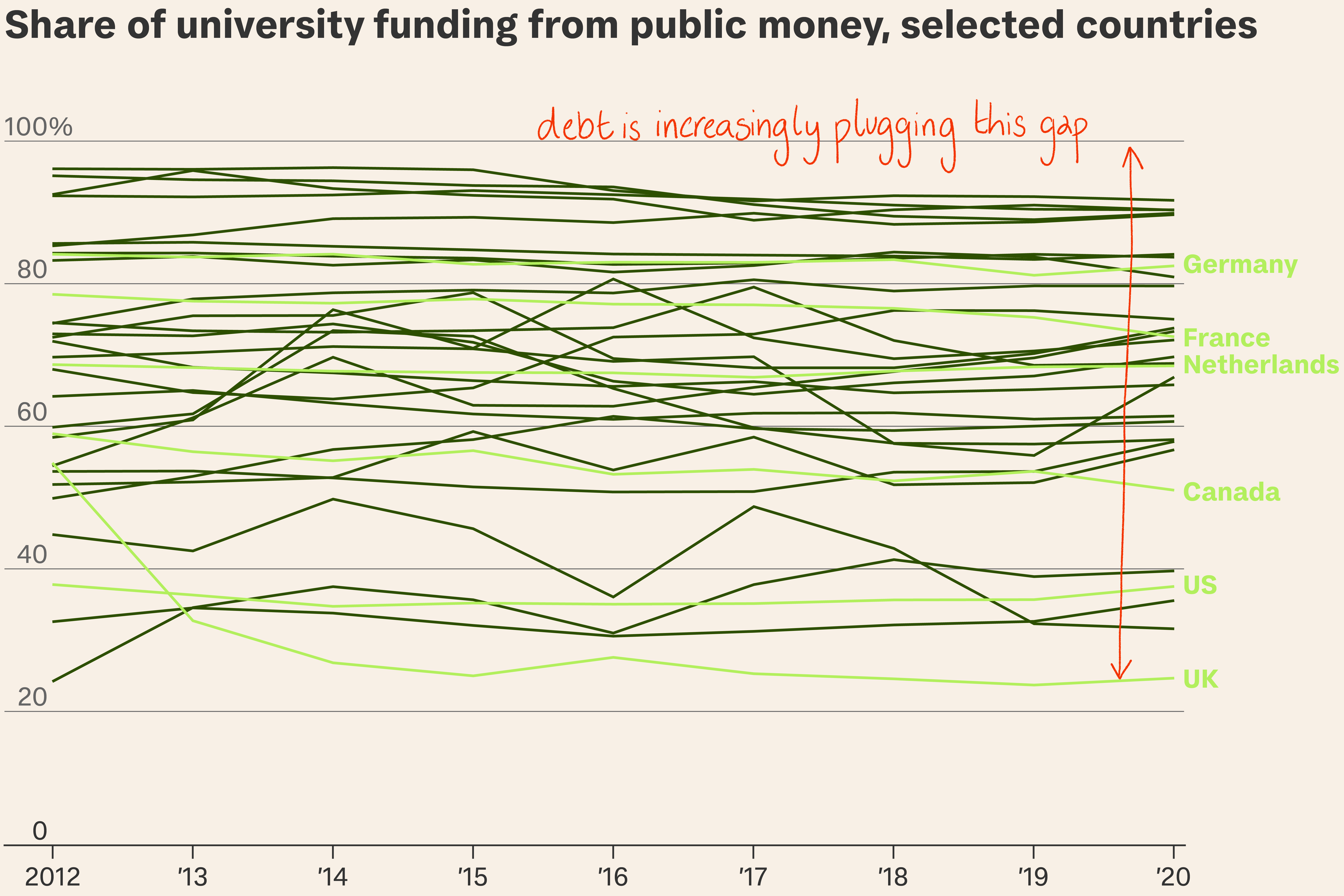

Education, just not that education. Universities are hemmed in by government policies. Over the last decade, the government has cut funding for teaching by 78 per cent and capped student loans at £9,250, leading to a real-terms decline in domestic fee income of more than a third. In the past three years alone, inflation has eroded universities’ resources by a fifth, with no equivalent of the per-pupil uplift given to schools.

Overseas investment. UK research bodies pay 80 per cent of university research budgets. The rest is expected to come from teaching income. The government’s ambition for the UK to become a science and technology superpower is thus at the mercy of course choices by overseas students who used to account for 20 per cent of the sector’s income.

If you book them, they won’t come. Even Russell Group universities now get most of their fee income from international students, the Sunday Times reports. But this academic year, international student numbers fell by 40 per cent:

- Nigerian students, previously the fastest-growing group, have fallen by 71 per cent thanks largely to a collapse in value of the Nigerian currency.

- Chinese student numbers are falling because of political tensions.

- But the biggest factor is the Sunak government’s ban on masters students bringing family members to the UK. Most overseas students come to the UK for postgraduate courses.

Cut jobs, cut rankings: The government is hoping universities will find productivity gains to cover rising costs. Vice-chancellors see job cuts as the main way to save money. But UK universities punch above their weight thanks mainly to staffing – British universities have on average 13 students per lecturer. In Canada that’s 23:1, and in Australia, 34:1.

The loans don’t work. The UK has the most indebted graduates in the world. Over 90 per cent of UK graduates take out a loan, accumulating an average debt of around £45,600. 60 per cent of US graduates take out a loan, with an average debt of $28,400. The UK government contributes the least to a student’s education of any OECD country. On average across the OECD, students pay roughly 30 per cent of the cost of their education and governments roughly 70 per cent. In the UK that’s reversed – 72 per cent from students and less than 25 per cent from the government.

So let’s make them worse. Last year the government changed repayments for student loans starting in 2023. Graduates previously stopped paying back after 30 years. That’s now 40 years. Overall numbers of students accepting places fell by 1.5 per cent in 2023 to their lowest level since before the pandemic.

What’s more… In August 2023, education secretary Gillian Keegan announced a “crack down on rip-off university courses,” while “boosting skills training and apprenticeships provision”. Government help for universities seems unlikely.

This piece was amended on 27 March

More than 70 countries are holding elections this year, but much of the voting will be neither free nor fair. To track Tortoise’s election coverage, go to the Democracy 2024 page on the Tortoise website.