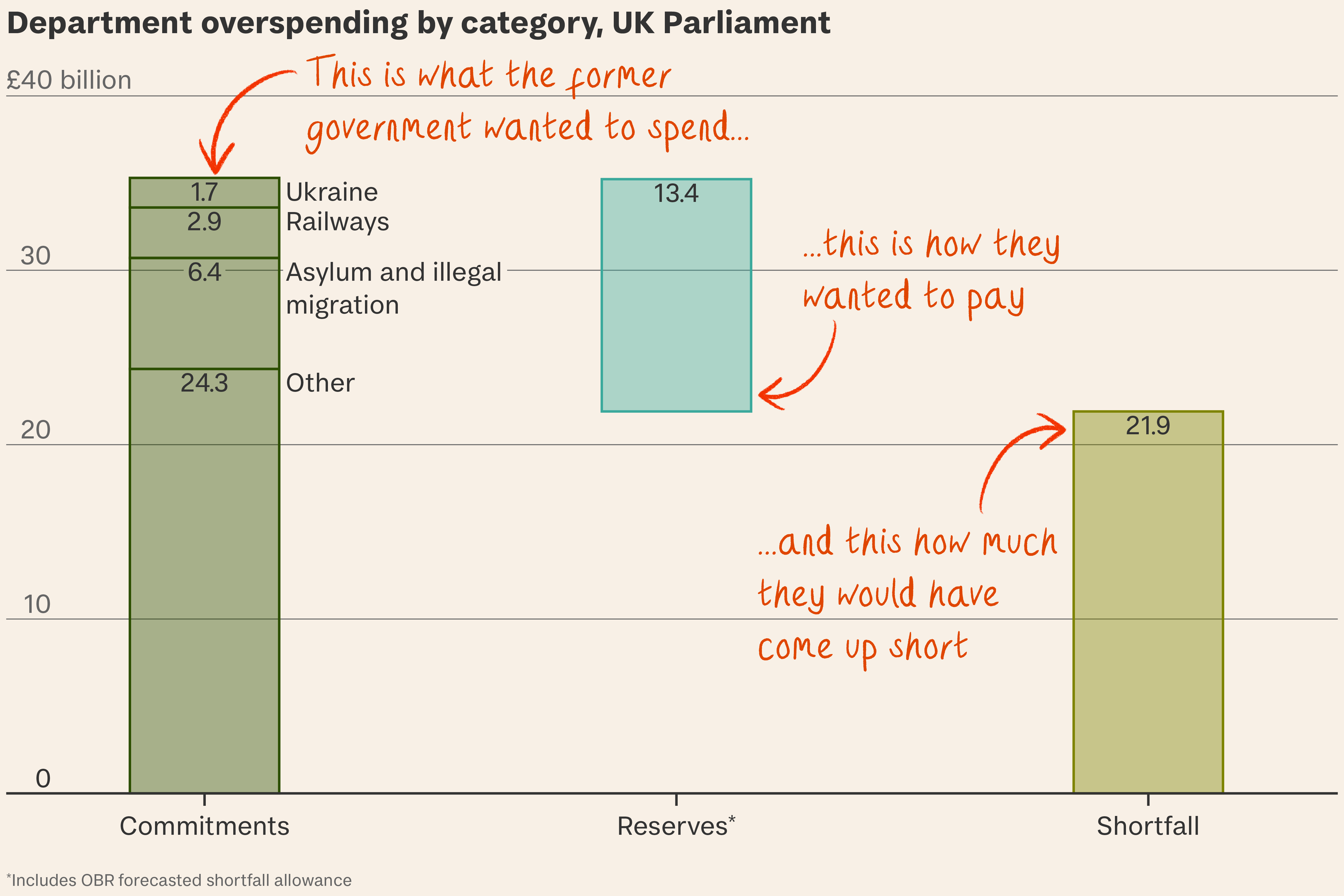

Chancellor Rachel Reeves has laid out plans to fill a £22 billion fiscal hole she claims to have inherited from the previous Conservative government.

So what? Reeves has been carefully sweeping up skeletons ahead of her first budget, which is now scheduled for the day before Halloween. By conducting her own audit of the previous government’s spending she is attempting to

- cement a narrative that the Tories hid the full extent of their damage to the economy;

- give herself political cover to hike capital taxes; and

- make a headstart on the onerous task of cutting public spending.

Playing dumb. Experts say the state of public spending shouldn’t come as a complete shock to the chancellor. Nearly half of the “hole” is made up from public sector pay rises – and that doesn’t include the full amount set aside for a 22 per cent pay bump for junior doctors announced yesterday. During a period in which private sector earnings are growing at 5 to 6 per cent per year, it was inevitable that pay awards would come in higher than the 2 per cent budgeted by departments.

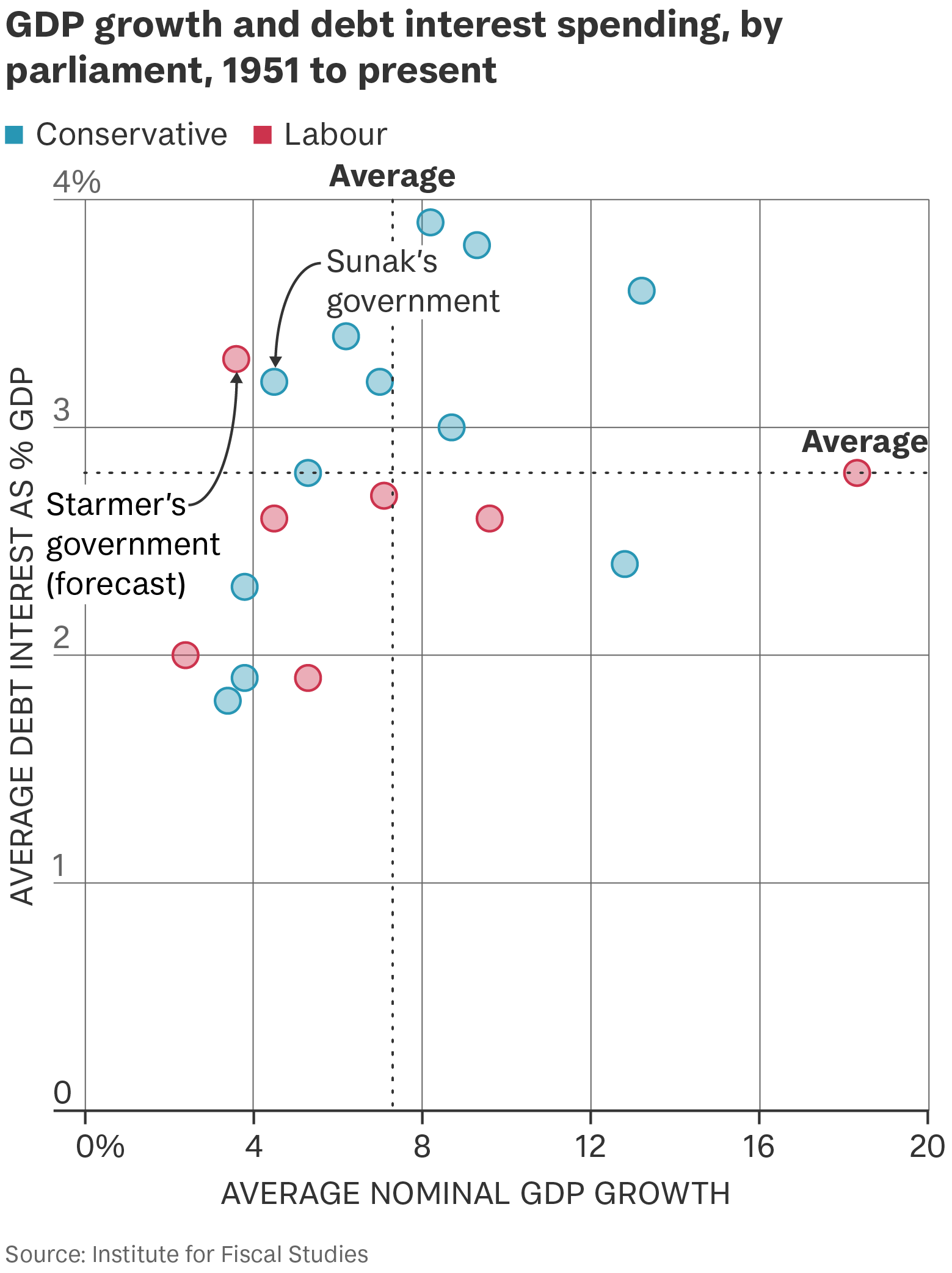

That said, the scale of overspend is a surprise, particularly the extra £6.4 billion spent on supporting the asylum system. Even Paul Johnson, the Cassandra-like director of the Institute of Fiscal Studies (IFS), conceded this “does genuinely appear to have been unfunded.”

Thomas Pope at the Institute for Government agreed. “There are usually bits of budgets that are a bit higher than expected and other departments will get squeezed… but we’re normally in the single digit billions – not £20 billion,” he said.

This begs the question why the extent of the problem never made it past the doors of the Treasury. Reeves insisted that the supermassive black hole was all down to the Tories. But senior civil servants may yet face some uncomfortable questions.

Falling axes. The refrain from the chancellor during her speech was “if we cannot afford it, we cannot do it”. In light of these additional spending pressures, the government has pledged to “fix the foundations” of the economy and has binned a number of Tory projects including

- winter fuel allowances for 10 million pensioners not on benefits;

- the A303 Stonehenge tunnel, the A27 south coast road and the ‘Restoring Our Railways’ scheme;

- the Rwanda migration partnership and retrospection of the Illegal Migration Act; and

- the retail share sale of the government’s holding in Natwest.

The biggest slice of savings suggested by the Treasury, equivalent to £3.1 billion in 2024/25, will come from unspecified cuts to departments. Reeves has laid out targets to reduce administration budgets by 2 per cent and to end all “non-essential” spending on communications and consultancy services. Cue jockeying by ministers to escape the worst. If the previous experience is anything to go by it’s probably local government that will bear the brunt of future cuts, rather than protected budgets for health and defence.

Austerity 2.0? Not yet. But when asked about further spending cuts, tax hikes and welfare reforms Reeves repeatedly talked about “difficult choices” to come. That’s not a code that needs deciphering.

Goodbye to growth? Having promised voters they would grow the sluggish economy, Reeves insisted she was still committed to the same fundamentals, reeling off a number of changes such as planning reforms that will help. “There is nothing pro-growth about abandoning a commitment to sound money,” she told reporters on Monday evening.

Elephant in the room. Long before Reeves stepped inside the Treasury, the challenge facing the chancellor was clear. In May, the IFS outlined the “inevitable tradeoffs” between cutting spending, raising tax and – whisper it – raising debt.

What’s interesting is Reeves’s decision to emphasise the profligacy of the Tories – and, in opposition, her own close-fistedness: “The markets would have eaten a slightly bigger borrowing level this year – what they really worry about is medium-term sustainability and that will be established at the budget,” said Pope. “Politically, to be shown to be taking immediate action and difficult decisions, helps to boost the chancellor’s credibility on fiscal discipline.”

What’s more. Reeves’s proposed “in year” savings total £5.5 billion. But even if they materialise, there’s a possibility that budgets will need topping up. Hunt’s £10 billion cut to National Insurance looks like an increasingly heavy cross to bear.